I’ve been replaying older RPGs as a form of stress relief due to the current crazy world. It’s a fun diversion, and I thought some people might enjoy my thoughts on decades-old RPGs. Final Fantasy IV, originally released in the United States as Final Fantasy II, is a classic of the SNES library even with a few flaws.

Two import notes before we begin:

- This is a an over 30 year old game, and there will be spoilers!

- I’m sticking with the name ‘Final Fantasy IV’ for this review except when specifically discussing history. My screenshots were taken from older versions labeled as Final Fantasy II, but it’s been decades and the game is IV on any current rereleases or collections. This American release was also based off an ‘Easy Type’ Japanese release, so a few elements were simplified or removed.

Let’s take a look at this top-tier game from the Super Nintendo era:

Prologue: Final Fantasy and Storytelling #

I feel this game should be remembered as an attempt to move from the more straightforward player-driven story of the original Final Fantasy to a cinematic storytelling experience that would become the standard for the franchise.

I first played Final Fantasy IV (under the Final Fantasy II name) around 1990-1991. I think a friend and I rented it and we played most of it, but couldn’t quite finish it. I’d later get a used copy to more fully explore: I may not have gotten my copy until the waning years of the SNES, which traveled with me as I went to college even as the Sony PlayStation became the defining console of the era in no small part due to Final Fantasy VII.

I came into the game with a background as a tabletop RPG fan. Perhaps not as nuanced as a more experienced gamer, but I’d been playing Dungeons & Dragons, Shadowrun, and various other tabletop games in the traditional “hack & slash” style common to many younger gamers. These games, primarily Dungeons & Dragons, clearly inspired the Final Fantasy series in many ways: There’s some monster art that looks very similar, a focus on elemental powers, and the basic “level” system.

The prologue of Final Fantasy IV is a series of scripted scenes followed by a playable “tutorial area” familiar to those accustomed to newer games.

The scripted scenes use in-engine scripting, which seemed novel for the time: Characters move around as little sprites on maps in a similar way to how the player controls the party on the maps. There’s occasional sprites to support “special effects” like characters being thrown around but in general the same sprites are used as in the actual playable game. It’s an effective storytelling tool augmenting the sparse dialog of the earlier games with tiny scenes featuring broad character movements. For the medium of cRPGs it had an impact I’d consider similar to movies adding sound. Also it helps make the player feel involved with the cut scene instead of just ‘watching a movie’ like later cut scenes.

The game starts with a scene of airships flying featuring the Super Nintendo’s Mode 7 effects. This allowed the world map to be rotated and portrayed as a surface the ships flow over. This ships land and we meet our protagonist.

The primary protagonist, Cecil, begins well-equipped and with a actual character levels. To fulfill the mandatory quota of analogies to Star Wars, he’s not Luke, the untrained farm boy dreaming of adventure. He’s more Han Solo, the seasoned veteran.

Except he’s not. He’s Darth Vader .

Our protagonist begins dressed in blue-black armor with a face-hiding helm. He’s enforcing the will of the king he’s sworn to serve. He’s strong-willed and focused on duty and protecting his troops.

Even Cecil’s crew questions his motives in the prologue as they steal the Mysidian’s crystal.

Cecil the Dark Knight is introduced to players via dialog and scripted combats. He defeats the Mysidian elders without even changing to the game’s ‘fight scene’ interface then defends his airships in battles scripted to showcase Cecil’s abilities. The player is an observer at this point, limited to pressing controller buttons to acknowledge the dialog, but little more.

Arriving home, he’s presented to the King of Baron where he voices his concerns. There’s a cinematic use of camera control where we see the discussion between the King of Baron and his advisor Baigan discussing the problematic Dark Knight before Cecil enters and voices his concerns. I mention this because it’s a break from the game conceit: Despite following Cecil, whom we will shortly control, we pull back and are briefly an omniscient viewer, viewing scenes our protagonist is not aware of.

Cecil is removed from command and sent to deliver a package joined by his companion Kain.

At this point the player assumes control. The castle and town of Baron to the village is somewhat similar to the ’tutorial area’ common in many cRPGs. The player can choose to grind by fighting the relatively weak monsters in the area or rush to the goal. It’s a ‘slice’ of the larger game allowing the player to learn how the game works, build up characters, and explore the world including a castle, town, and eventually the cave leading to their goal. The Knights of the Old Republic single-player games both had long introdcutory sections where the player’s world expanded slowly. The trip to the village is an example of this concept but doesn’t feel restrictive. Eventually Cecil reaches the village, unleashing a firestorm as ‘The Package’ activates and chaos ensues.

Act 1 #

Final Fantasy IV is a major leap forward from the original game in many ways. I’m focusing on the cinematic aspects here, but the capabilities of the SNES allowed for massive improvements in graphics, sound, and details of the world. Multiple sprite layers are used to allow walking behind scenery. The airships fly using the Super Nintendo’s Mode 7 to provide a simple 3d effect to simulate flying around above the surface of the world.

I personally feel like the SNES era was a golden age for sprite-based game graphics. The sprites are detailed, but the player is still able to fill in the details. The game’s manual included concept artwork presenting the characters in a more specific canon style, but the sprites are open to interpretation. Newer 3d-based games lose this virtue in my mind.

This game is written as a cinematic story compare to the earlier Final Fantasy. The earlier game resembles a sprawling early D&D adventure. The original Final Fantasy had the player create four characters, choosing from a range of classes, which were interchangeable in terms of the plot. Each was just one of the ‘Light Warriors’ who acted as a group.

Final Fantasy IV is written with a cast that comes and goes as their own motivations and actions require. Cecil is the protagonist, but joined by various companions throughout the story. The characters who join the party are listed below:

-

Kain: A Dragoon (A recurring trope of the series established here: In the real world Dragoon is a term used for a kind of cavalry military: here it’s as armored spear wielders who can jump, often with the ability to be “off screen” for a lengthy period, before making a strong attack against an enemy.) who joins briefly before spending a great deal of the game as the brainwashed minion in service to the enemy. He is freed and rejoins for the climax.

-

Rosa: Cecil’s girlfriend and White Mage (a wizard specializing in healing magic). After being saved from poison she joins the party but is later kidnapped and held for ransom.

-

Rydia: The young girl saved in the prologue. She is a ‘Summoner’ with access to magic as well as unique access to a selection of powerful monsters that can be summoned as special attacks. She is ’lost’ when Cecil’s team is attacked during a trip on a sea-going ship, then returns to the part having grown up and become much more powerful.

-

Tellah: An old man with the class of ‘Sage’ he has access to many spells. He’s even forgotten several of them. His daughter Anna is in love with Edward causing friction. He joins Cecil a couple times, eventually learning the spell ‘Meteo’ and using it to weaken Golbez. He is written as an example of allowing vengeance to guide one’s actions.

-

Edward: Edward is only in Cecil’s party for a short time. A prince, he joins the group after Tellah’s daughter Anna is killed. After his time in the party he’s injured, but provides a melody that allows a boss to be defeated. Edward is interesting as he’s nearly useless in combat: Once he’s sufficiently injured, he auto-triggers a special ‘hide’ command that has him run from the combat. Recovering from this mid-combat is nearly impossible as he can’t be healed when he’s “off screen.”

-

Yang: A martial artist, his home castle is destroyed shortly after Cecil’s team finds him. He ends up sacrificing himself to destroy a massive cannon but can be restored by using a ‘Frying Pan’ item acquired from his wife to wake him up. He’s aprt of the well-wishes in the final conflict.

-

Palom: Always seen with his twin Porom, this is a wizard specifying in offensive black magic. The two are assigned for Cecil’s quest to Mount Ordeals and later sacrifice themselves to stop a pair of crushing walls.

-

Porom: Palom’s twin, she is skilled in curative magic. With her twin they have a powerful paired attack spell that suggests later ‘combo’ abilities seen in later cRPGs. They’re restored from their sacrifice but limited to being part of the wishes for the finale. (Palom and Porom were the heart of an urban legend for this game. They sacrifice themselves by turning themselves to stone to stop crushing walls. If the player investigates they’re given a prompt to use an item: no items work. This was believed to be cut content from the ‘Easy Edition’ used for the English release, but reports have confirmed it was not functional in the original Japanese edition, either.)

-

Cid: Starting a recurring gag for the franchise, ‘Cid’ is often a character associated with the airships of each game. Cid joins the party for a brief sequence but ends up busy doing off-screen upgrades and such. Cid’s only in the party for a short time, which is fine as he’s really not that amazing in combat.

-

Edge: Edge is a ninja and the second prince of the game: He’s given a short arc as he realizes he needs to work with the other heroes and ends up as part of the final roster at the end of the game.

-

FuSoYa: Another wizard, FuSoYa joins for a brief segment from when he is reached on the moon to when the party stops the a giant robot in the Tower of Babil.

The characters exist mechanically as different tools to overcome challenges, but they’re also given brief plot arcs with their own challenges and triumphs.

Cecil ends up separated from Kain, but with the young girl met in the village. They travel to a desert town. She’s Rydia, and is interesting for the next section as she’s very weak when she joins the party. This is a contrast from Cecil and Kain’s experienced status. The player can choose to spend time leveling her up which grants her access to a wider range of magical spells, but it can be difficult as she is very vulnerable at first.

Cecil and Rydia eventually find that Cecil’s girlfriend Rosa is in desert town. Searching for a cure, they become involved in Edward and Tellah’s feud over the sage’s daughter, Anna. She is killed when Cecil’s former troops bomb a castle. Tellah leaves to pursue revenge while Edward helps heal Rosa and travels with the group warn others about the crystal thefts. We meets Yang, a martial artist, and unsuccessfully fight to defend Yang’s home of Fabul from former friend Kain, now working for the enemy. They learn that Golbez is the new leader of the Red Wings and the puppet-master behind the crystal thefts.

The group takes a ship to Baron but the vessel is attacked. We’re left to wonder about everyone else’s fate as Cecil wakes on the shores of Mysidia, the town he raided in the prologue.

Act 2 #

Supporting this larger cinematic vision is a new engine supporting a range of features. Similar idiom would dominate the cRPG market for much of the Super Nintendo’s life. As has already been said, the SNES offered improved graphics and sound from the earlier feature. The heart of the new game was the premier of Active Time Battle, a patented mechanic used for several games extending into the Playstation era.

“ATB” replaced the previous system where the player made choices for battlefield actions for their entire party and the game then resolved those actions and those of the monsters. With ATB, the player would be asked for an action whenever a character’s turn came up. There was a delay between entering a command and the command occurring. It made combat more interesting and more stressful (in a good way) as it tasked the player to consider timing.

Many tabletop RPGs used something akin to the pre-ATB system and, amusingly, players often adopted something more “ATB like” finding it more fun. Later editions of D&D (and many other games) would enshrine this and craft themselves around the concept.

The original Final Fantasy was also set up that targets were fixed. This meant if all four player characters attacked a specific monster, they would waste attacks if the monster was defeated mid-way through. I think some later pre-ATB games resolved this by having attacks fall throguh tot he next target, but it could lead to frustration.

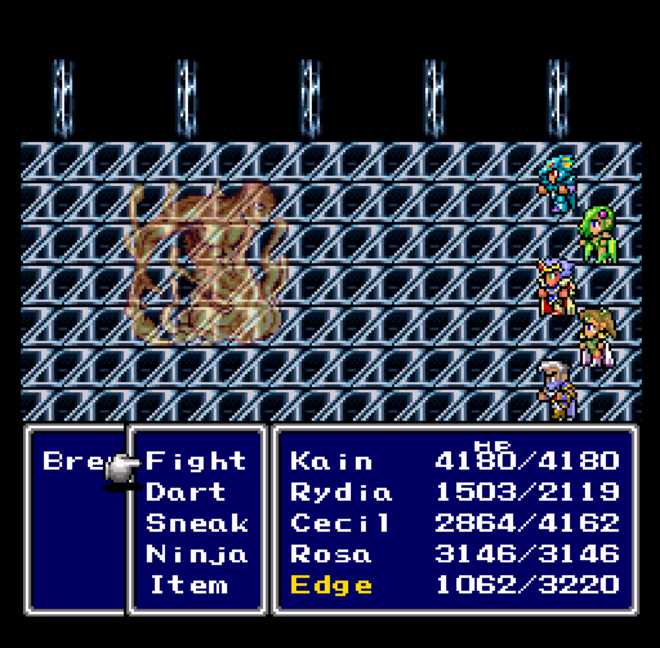

The Final Fantasy IV engine allowed for five PCs in the party. The engine allows for a ‘surprised’ state where the party is moved from its usual state on the right side of the screen to the left. This interacts with the game’s limited concept of ‘party ranks.’

In the image above Rydia and Rosa are in the back rank. This means they take less damage, but also do less melee damage. There’s a ‘hidden’ Change command that allows the two ranks to switch in combat, which is useful if the party is ambushed: Move the party to the left side of the screen and now Rydia and Rosa are exposed on the ‘front line’ while the tougher combatants are hindered. (All of this is configurable out of combat. The game forces the ‘3/2’ split but the player can move characters around of decide if the three character or two character group takes the lead.)

All characters have a ‘Fight’ and ‘Item’ command along with ‘hidden’ commands to ‘Change’ (swap the ranks for all characters) and ‘Run’ (to try and flee combat). The other three commands vary by character. Edge is acting here and can sue Dart to toss an appropriate item at an enemy to do massive damage, Sneak to evade attacks, or Ninja to access a small selection of Ninja magic.

The Item command can be used for the normal healing potions and similar. It can also be sued with a somewhat hidden command to change held equipment: Characters can switch weapons mid combat! Rosa, for example, specializes in the bow and can sue this command to equip various arrows.

Character’s spells can accessed through the status interface between combats as well. An odd feature of the game is each character’s spells can be reorganized independently: The spells are added in the order learned, but the player can sort them into a neat, orderly list if they choose. It’s an odd feature, especially as characters often have the same core lists to draw from (Rydia, Tellah, Palom and FuSoYa all have access to Black Magic for example) and may only be in the party for a short time. It feels like an odd extravagance and I don’t know of any later games that maintained it. Perhaps the developers felt it was necessary due to the increased pressure of the Active Time Battle system.

Similarly the (shared) equipment list can be sorted. An odd behavior is that it doesn’t automatically combine items: if the player buys ten potions individually, they will take up ten spots on the very limited list of equipment carried. At least there’s a sort command and a ’trash’ icon to combine items and put the usable stuff near the top, or get rid of unneeded stuff mid-adventure.

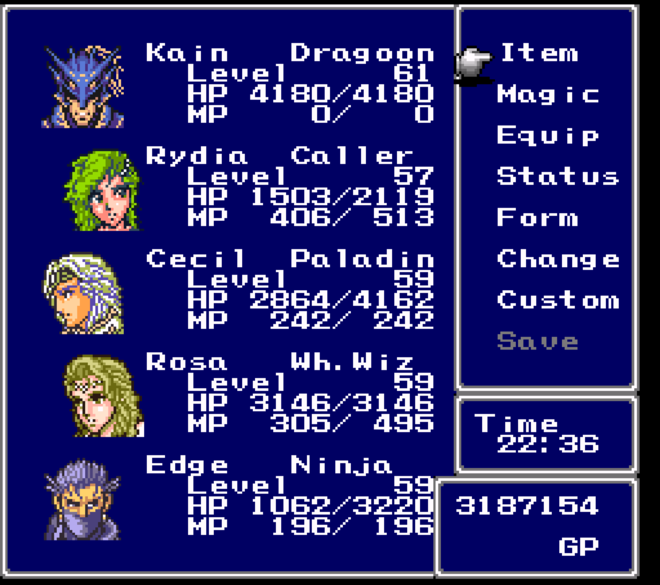

This Status screen also shows the use of larger portraits for characters. Later games often built off this idea and used the portraits to adorn dialog displays, adding additional head-shots to show character’s emotions. Here they’re static (with the exception of Cecil and Rydia who develop in their storylines) but still show characterization. Cecil is presented here as calm and focused compared to edge’s more uneasy appearance.

Cecil is predictably unwelcome in Mysidia. Random residents cast spells on him if talked to, so Cecil may spend some time as a pig or frog as he explores the town. Eventually the elders give him a quest to prove his worth: He must travel to Mount Ordeals to prove he’s changed his ways. He’s accompanied by two kid wizards, Palom and Porom.

In an inversion of the prologue, his Dark Knight abilities are now a hindrance due to the many undead enemies found here who take minimal damage from his weapons. He must rely on Palom and Porom and later Tellah as he climbs to the top.

The climb also includes the first of the four fiends bound to Golbez: the fiend of Earth. The classical elements are a common trope in Final Fantasy games. In any games they’re the basis for magic spells and damage. Often they form the basis for themed dungeons. The Earth Fiend, known as Milon in the original game, is first encountered as a sort of robed entity reminiscent of the disguised evil queen in Snow White. After being defeated he returns as a strange undead monster. I remember initially interpreting the sprite as shaving elements of a mammoth but later art suggests the pale yellow elements are meant to be tentacles or spines instead of tusks. He has many cues suggesting an ‘undead’ motif.

Cinematically, it’s a reference to the common horror trope of “You thought he was dead, but…”

At the top of the mountain is a mysterious door that, it must be said, resembles some sort of high-tech port-a-potty. Here Cecil must fight the darkness within himself and while that was not totally new in gaming even then (See Zelda II: The Adventure of Link), it is an emotional and moving moment. it’s at this point that Cecil does truly become the genre favorite ‘chosen one’ and learns he has a destiny. We even get a one of the games rare breaks to show a full screen of text to explain the newest turns in the story.

“Upgrades” like this are something of a Final Fantasy trope: The original game used a similar mechanic but instead all characters became the advanced version when they completed a specific quest. Here we’re focused on Cecil. Tellah gets a minor boost (learning the ultimate damaging spell ‘Meteo’) but Cecil is a hero reborn: A new set of sprites and portraits replacing the faceless blue-black helmet with a more colorful look that shows off flowing locks, a reset to level 1, and new equipment.

(Rydia “grows up” when she returns to the story, but her change still seems less spectacular.)

Cecil the Paladin quickly catches up to his former level, but he’s very different: He has some healing spells similar to those of the other casters such as Rosa, but also has an automatic defensive ability; He’ll often interpose himself to prevent his allies being injured, taking the hit instead.

At about this point I feel like the story becomes less obviously linear: There’s a main path, but the player is given much more freedom in no small part due to being given an airship to control. There’s a lot that happens in this segment, and I’m not even trying to summarize it in any detail. If there was a movie trailer a deep-voiced narration would run over scenes including:

- Cecil returns to his former home of Baron.

- Fighting Kainazzo the Fiend of Water.

- Reuniting with Cid, who gives Cecil his airship.

- Reaching the underground Dwarf kingdom.

- Fighting Creepy Dolls.

- Storming the Tower of Babil with Dwarf tanks supporting in the background.

- Fighting another fiend, Valvalis the Fiend of Air

There’s a lot and I’d consider the final act when the party makes their second foray into the underworld and meets Edge, a prince and ninja. They again end up in the Tower of Babil and defeat the fourth fiend, Rubicant. There’s another betrayal by Kain as he’s mind controlled again. All seems lost, but as in so many epic stories, there’s a tiny glimmer of hope and light.

Act 3 #

Final Fantasy IV set the bar for a lot of later cRPGs for the SNES platform and beyond. The pixel art works extremely well. It’s configured so there’s a background layer and a foreground layer, allowing the player to go behind buildings despite the pseudo-3d look. Trees and walls obscure the player’s sprite (which can be changed to any current party member with a tap of the SNES controller’s shoulder buttons) but allow enough to be visible. Hidden passages are just barely visible, making the player feel clever.

There’s some odd experiments, like the previously-discussed feature to support manually sorting spells.

The four vehicles (2 airships, a hovercraft, and the Big Whale) are fun but can be frustrating to manage, especially if you forget where you left one! You generally don’t need the later ones, but the Hovercraft does have some utility long after it’s initial use.

The cinematic changing cast is a huge aspect of the game. It does lead to some potential frustration: Cid and FuSoYa are only in the party for a short time, for example, so effort developing him is probably not worth it. In the original you never get any real choice on your party: The game dictates who you will use for various sections. There’s a few options to focus on side quests while a specific character is in the group, but this is minimal.

Hope comes as the Mysidians summon the Big Whale which is, essentially, a spaceship. It’s an Airship, but also a ‘base’ (with a bedroom and access to the Big Chocobo storage system inside) and, most importantly, it’s able to fly tot he moon.

The moon is the final region the party explores, although there’s options to travel back and several side quests that are recommended to help power up the party for the final battles. A temple-like structure has a familiar ‘crystal cavern’ and a kindly old man named FuSoYa who hands out exposition before joining the party as another spell caster. Cecil now knows he’s the brother of the villain Golbez and their father was one of the moon-people.

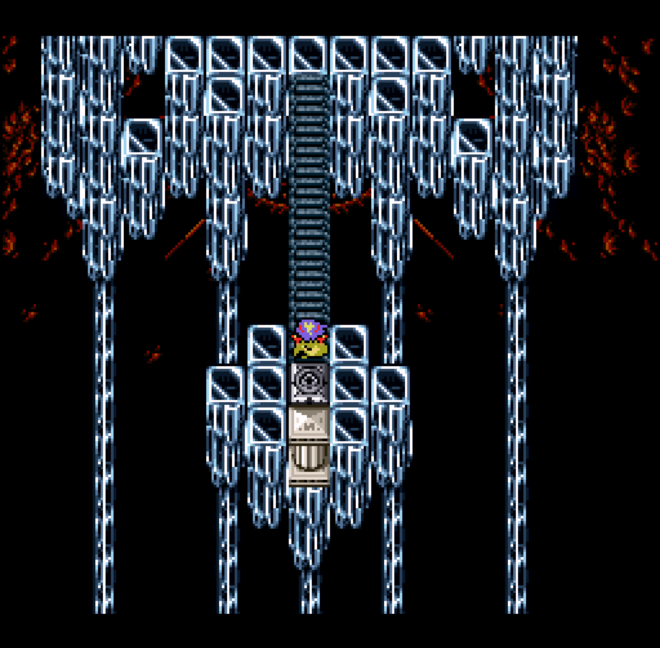

Golbez, and Cecil, are focused on the ‘Tower of Babil’ which has a sci-fi look inside and, eventually, releases a giant robot intended to remove the troublesome inhabitants of the world so moon-people can move in.

The story has evolved from a dark knight questioning orders to a band of heroes opposing ancient immortals from the moon.

Golbez, like Kain, is revealed to have been mind-controlled. He’s defeated and goes off with FuSoYa to try and fix things, but the player certainly knows they’ll need to do most of the work. The true enemy is Zemus, an angry moon-dweller. The party delves deep into a final dungeon to defeat him, exploring deep beneath the moon’s surface. They reach Zemus just after FuSoYa and Golbez, who are unable to defeat the monster despite their powerful abilities.

Cecil and friends jump into the fray but seem defeated as well until prayers and well wishes from many friends (including several characters that had previously been in the party) give them the strength to go on. The party defeats Zemus with another ’trick fight’ but the real fight is his angry second form as Zeromus. It’s an epic fight and victory will feel like an accomplishment.

Epilogue #

Wrapping up this perhaps over-long review, I think this game is often ignored in favor of the better known Final Fantasy VI which is, of course, overshadowed by the PlayStation-era Final Fantasy VII which entered the 3d era. Both of these games maintained and strengthened the focus on cinematic storytelling. FF VI (released as Final Fantasy III in the United States) gives the player a bit more control. From memories it tries to ‘hide’ the maximum character limitation for much of the game, but in the final act I think it just admits the limitation of the game engine. Many later games would take this route, simply saying that there’s a limit to the active number of characters.

Unlike many Final Fantasy works this game did receive a direct sequel, albeit many years later. In 2008 Final Fantasy IV: The After Years was released as an episodic mobile phone game. It would later be enhanced for release on a wide range of platforms. To my understanding the initial release retained the pixel art style of the original, but the currently-available IOS version is rendered in a low-poly 3d style somewhat reminiscent of the later Final Fantasy 7. I want to play this at some point: It’s considered an interesting continuation of the original game.

There is an epilogue as we learn Cecil and Rosa are married and have taken the throne of Baron, while Kain is off dealing with his guilt for the things he did while under Golbez’ control.

Thanks for reading this! I hope to follow up this review with some other classing cRPGs: More Final Fantasy, Chrono Trigger, the Baldur’s Gate series, and more.